Lumbar Spine Surgery

Microdiscectomy

This is a minimally invasive procedure that allows decompression of a nerve in the spine that has become jammed by a herniated disc. A small incision is made in the back to enable a corridor to be created between the muscles and the spine and then a small window into the spinal column itself (via what we call a laminotomy). This then allows the nerve to be seen and the disc fragment removed. If the situation is one where the nerve is jammed by bony spurs (foraminal stenosis) the procedure involves a general widening of the channel through which the nerve is passing so that the nerve has more room. An operating microscope is used to allow this microsurgery to be performed. Xrays are used in the procedure to allow precision and accuracy.

Most patients can expect to stay one night in hospital, roughly one week where they can take care of themselves at home but not doing anything heavy (i.e. no vacuuming, bed linens, gardening, or carrying more than 3 kg), and roughly one month gradually increasing back to normal activities in a common sense fashion. Return to desk work is usually within the first one to two weeks although more physical work should be delayed until four to six weeks to make sure that enough healing has occurred before the spine is loaded.

When properly assessed beforehand this treatment option can be very helpful at relieving the symptoms of radiculopathy if they are not settling with non-surgical treatments.

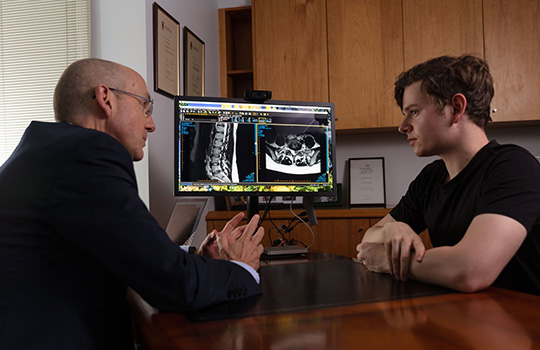

Dr Brennan is highly trained and experienced in the surgical treatment of conditions of the spine including spine tumours

Lateral Recess Decompression and Lumbar Parsectomy

This procedure is performed most often to decompress a nerve that has become jammed by arthritic spurs due to spondylosis. It is similar to a microdiscectomy (explained above) except that goal is to generally widen the nerve exit hole and clear away overgrown spurs to create space for the nerve.

In the low back decompressing the nerve root foramen may take the form of widening or “unroofing” the lateral recess where the nerve may become jammed by spurs, cysts or other arthritic tissue. In situations where the nerve root exit foramen itself is narrowed by bony spurs (sometime called the syndrome of the superior fact) or by a disc protrusion (an “intraforaminal” disc herniation) decompression can be achieved by opening up the back wall of the foramen via a procedure called a “parsectomy”), or a combination of a parsectomy and a lateral recess decompression depending on the exact location of the problem as revealed on the preoperative MRI or CT scan.

The approach, surgical equipment required, and recovery is very similar to a microdiscectomy. The difference lies in what needs to be done in order to decompress the nerve as determined by a careful and proper assessment of the history, examination, and scan findings.

Lumbar Laminectomy

This is somewhat of an umbrella term referring to a number of procedures that can be done in the lumbar spine. These operations share the fact that they are performed through an incision in the back that is tailored to allow removal a portion of the bone at the back of the spinal canal in order to unroof the space for the spinal nerves. This may be needed in order to decompress them in certain situations of spondylosis and spinal canal stenosis, but also to allow access to the spinal canal to permit the treatment of tumours, vascular lesions, or other surgical conditions in this location.

The amount of bone removed needs to be tailored to the individual situation so that enough space is created for the delicate neural elements. The guiding principal is to limit this the minimum required. Some patients may be surprised to learn that the human body can safely function even without this part of the spinal bone, but it has been well shown over many decades that this is the case and so laminectomy in one form or another remains a very common procedure in the treatment of spinal conditions.

Often, traditional or full laminectomy whereby the entire lamina of a vertebra is removed is not required. In many instances more minimal procedures such as unilateral laminectomy (performed on one side only), laminotomy (in which a small portion only of the lamina is removed), or interlaminar decompression (whereby a small portion of the lamina above and below the so-called level may be needed but the majority of each is preserved). There can be other variations such as bilateral decompression from a unilateral approach in which both sides of the spinal canal can be decompressed via a laminotomy performed on one side only. The correct choice of procedure depends on a careful and thorough assessment before surgery of the patient, the clinical features (i.e. the history and examination findings), and a nuanced interpretation of the imaging.

After surgery the recover depends to some degree on the extent of the laminectomy involved, but as a general rule the procedure is well tolerated with people remaining in hospital for usually a couple of nights and getting back into doing things over the two to four weeks after discharge.

Lumbar Spinal Fusion Surgery and Spinal Stability

Spinal fusion refers to the joining up of one bone in the spine to another. It often involves a combination of placing internal fixation or “instrumentation” (e.g. screws, rods, or plates) and bone grafting (either bone taken from the spine or somewhere else in the body, or bone graft “substitutes” that function in a similar way). The purpose of the instrumentation is to achieve immediate stability by holding the bones together in a solid fashion, while the bone grafting allows the process of healing by fusion to proceed over the coming months. This process is very similar to fixing a broken bone where some form of hardware may be needed to immobilise the fracture while the body then heals the break over time.

The goal of spinal fusion is to provide the spine with the stability it needs that it may have lost as a result of the particular disease or condition requiring treatment. The concept of “stability” is best defined of the ability of the spine to do its job, which in turn is generally understood to mean the ability to protect the spinal cord and nerves, to allow a solid basis for movement across the body, and to do so while also minimising the possibility of long term pain or deformity. Certain conditions or injuries can compromise the ability of the spine to perform this function, and we refer to this as the spine having become “unstable”. In some situations this may lead to excessive or abnormal motion or alignment between one level of the spine and another, and these so called “dynamic” factors may contribute to the problem that ends up needing an operation to treat. As part of the goal of the surgery in these situations spinal fusion may be necessary to re-establish the stability of the spine, to re-align and correct deformity, and to prevent further injury from these uncontrolled dynamic forces.

Placing implants or “hardware” during the course of spinal fusion can be assisted with the use of spinal navigation particularly in some cases of lumbar and lumbo-sacral or pelvic fixation.

Fusion for its own sake has rightly developed a controversial name in surgery mostly due to attempts in treating so-called axial spinal pain (neck or back pain WITHOUT nerve compression) where success rates are difficult to predict. However, in other situations fusion may be an important component of treating conditions that have led to the spine developing instability (e.g. injuries, arthritis, infections, tumours etc), or in order to reconstruct the spine after surgery done to decompress the spinal cord or nerves (usually performed at the same time).

Recovery from fusion surgery can take a little longer than from decompression surgery alone but very much depends on the extent of the dynamic factors or deformity that is being addressed (i.e. how many levels need to be treated, which part of the spine is involved, and whether there are confounding medical problems such as osteoporosis, excessive obesity, diabetes, etc). In some cases a period of planned rehabilitation or convalescence in a dedicated rehabilitation hospital under the care of a rehab physician may be beneficial as an interval step in the recovery process between leaving the acute care surgical hospital and before going home for further out-patient based physiotherapy etc.